DOUGLAS A. ZEMBIEC, MAJ, USMC

Douglas Zembiec '95

Lucky Bag

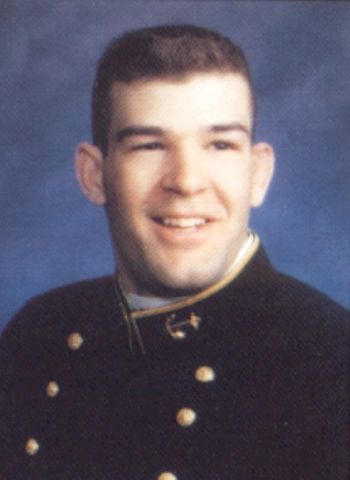

From the 1995 Lucky Bag:

Douglas A. Zembiec

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Molded from the Old School, fearless, dedicated, disciplined, SEMPER FIDELIS. Swam to spider buoy… twice. All-American wrestler. Always piping up at lectures. Stuck foot in mouth more than once… "Neurochlamydia." If only he could of had one hug…Nance. Weirdo relationship with Donovan, admiring each other's goods. Naked trip around Goat Court. Stood BRW from rack. Neanderthal man, physical monster, always training. Four idols: Ira Hayes, Sam Kinison, Conan, Ron Jeremy. Doug, what is best in life? "To crush your enemies, to see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their women!" The ULTIMATE WARRIOR.

Douglas A. Zembiec

Albuquerque, New Mexico

Molded from the Old School, fearless, dedicated, disciplined, SEMPER FIDELIS. Swam to spider buoy… twice. All-American wrestler. Always piping up at lectures. Stuck foot in mouth more than once… "Neurochlamydia." If only he could of had one hug…Nance. Weirdo relationship with Donovan, admiring each other's goods. Naked trip around Goat Court. Stood BRW from rack. Neanderthal man, physical monster, always training. Four idols: Ira Hayes, Sam Kinison, Conan, Ron Jeremy. Doug, what is best in life? "To crush your enemies, to see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their women!" The ULTIMATE WARRIOR.

Loss

Douglas was killed in action with Iraqi insurgents on May 11, 2007 while leading a raid as a part of the CIA's Special Activities Division Ground Branch.

Biography

From Wikipedia:

Early life

Doug Zembiec was born on April 14, 1973 in Kealakekua, Hawaii. He attended La Cueva High School in Albuquerque, New Mexico where he was a New Mexico State high school wrestling champion in 1990 and 1991. As a wrestler, Doug was the first time New Mexico State Champion in any sport and the first repeat winner at La Cueva High School. He was undefeated in competition his senior year.

He attended the United States Naval Academy where he was a collegiate wrestler compiling a 95–21–1 record and finishing as a two-time NCAA All-American. His fellow wrestlers sometimes referred to him as "The Snake" for his anaconda-like grip. Doug was well known amongst his contemporaries throughout his athletic and professional life for his exceptional physical fitness. His coach, Reginald Wicks, referred to him as "the best-conditioned athlete I’ve ever been around." Zembiec graduated from the Academy on May 31, 1995; then served in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1995 until killed in action in 2007 — serving combat tours in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Military career

Upon graduation from the Naval Academy, Zembiec was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps. After finishing The Basic School, and the Infantry Officer’s Course, he was assigned to First Battalion, Sixth Marine Regiment as a rifle platoon commander in Bravo Company, which was effective starting April 1996. After successfully passing the Force Reconnaissance indoctrination in June 1997, he was transferred to 2nd Force Reconnaissance Company, at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. As part of his training for Force Reconnaissance, he completed Army Airborne School as well as the Marine Combatant Diver Course. He served for two and a half years as a platoon commander, eight months as an interim company commander, and one month as an operations officer.

Zembiec’s Force Reconnaissance platoon was among the first special operations forces to enter Kosovo during Operation Joint Guardian in June 1999.

In September 2000, he was transferred to the Amphibious Reconnaissance School (ARS) located in Ft. Story, Virginia and served as the Assistant Officer-In-Charge (AOIC) for two years. In 2001, Zembiec competed in the Armed Forces Eco-Challenge as team captain of Team Force Recon Rolls Royce.

From ARS, Zembiec was selected to attend the Marine Corps’ Expeditionary Warfare School in Quantico, Virginia graduating in May 2003. Following the Expeditionary Warfare School he took command of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division in July 2003.

He was named the "Lion of Fallujah" as a result of his heroic actions leading Echo Company 2/1 during Operation Vigilant Resolve in 2004. As a rifle company commander, he led 168 Marines and sailors in the first conventional ground assault into Fallujah, Iraq. He was awarded a Silver Star, Bronze Star with Combat Distinguishing Device and two Purple Hearts due to wounds incurred in action.

He turned over command of Echo Company in November 2004 and served as an assistant operations officer at the Marine Corps’ First Special Operations Training Group (1st SOTG) where he ran the urban patrolling/ Military Operations in Urban Terrain (MOUT) and tank-infantry training packages for the 13th Marine Expeditionary Unit in preparation for an upcoming deployment to Iraq. Zembiec transferred from 1st SOTG to the Regional Support Element, Headquarters, Marine Corps on June 10, 2005. His promotion to Major was effective on July 1, 2005.

Death

Zembiec was serving in the CIA's Special Activities Division Ground Branch in Iraq when he was killed by small arms fire while leading a raid in Baghdad on May 11, 2007. Zembiec was leading a unit of Iraqi forces he had helped train. Reports from fellow servicemen that were present in the dark Baghdad alley where he was killed indicate that he'd warned his troops to get down before doing so himself and was hit by enemy fire. The initial radio report indicated "five wounded and one martyred" with Major Zembiec having been killed and his men saved by his warning. On May 16, 2007, a funeral mass was held at the Naval Academy Chapel and later that day he was interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Grave Number 8621, Section Number 60. Zembiec is buried only a few yards away from his Naval Academy classmate, Major Megan McClung. McClung was the first female Marine Corps officer killed in combat during the Iraq War, and first female graduate in the history of the Naval Academy to be killed in action. Shortly after his death, he was honored with a star on the CIA Memorial Wall, which remembers CIA employees who died while in service. Although Zembiec's star officially remains anonymous as of July 2014, his CIA employment was confirmed in interviews with his widow and former U.S. intelligence officials.

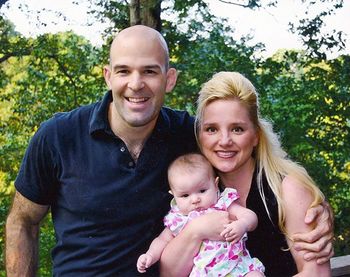

In July 2007, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates publicly lost his composure showing a rare glimpse of emotion from senior political leadership while discussing Major Zembiec during a speech. Major Zembiec was also prominently featured in a high-profile Wall Street Journal column in September 2007. In November 2007, Zembiec's high school Alma Mater, La Cueva High School, inducted him as the charter member of their Hall of Fame and named the wrestling room in his honor. The NCAA announced that Zembiec would be awarded the 2008 NCAA Award of Valor. In January 2008, General David Petraeus, Commanding General Multi-National Force – Iraq (MNF-I) dedicated the Helipad at Camp Victory located at Baghdad International Airport in Zembiec's name. He referred to Zembiec as "a true charter member of the brotherhood of the close fight." Douglas Zembiec is survived by his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Don Zembiec, brother, and his wife and daughter, Pamela and Fallyn.

On May 11, 2009, a petition was presented to the Secretary of the Navy to have the next Arleigh Burke class destroyer to be commissioned named after Zembiec.

The swimming pool located at the Marine Corps' Henderson Hall is named in honor of Major Zembiec.

By order of the Commandant of the Marine Corps, the Douglas A. Zembiec Award for Outstanding Leadership in Special Operations was created on April 11, 2011 to annually "recognize the Marine officer who best exemplifies outstanding leadership as a Team Leader in the Marine Corps Special Operations Community."

He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Quotes

Major Zembiec left many volumes of personal writings behind, some of which were shared at his funeral. The final words of the eulogy, delivered by his friend Eric L. Kapitulik, have evolved into a new credo for many members of the USMC, amounting to what Kapitulik said was a summary of Zembiec himself.

Be a man of principle. Fight for what you believe in. Keep your word. Live with integrity. Be brave. Believe in something bigger than yourself. Serve your country. Teach. Mentor. Give something back to society. Lead from the front. Conquer your fears. Be a good friend. Be humble and be self-confident. Appreciate your friends and family. Be a leader and not a follower. Be valorous on the field of battle. And take responsibility for your actions. Never forget those that were killed. And never let rest those that killed them.

Kapitulik said the creed came from the man who knew Zembiec the longest, as indicated by the Major's written description: "Principles my father taught me."

Other quotes:

Killing is not wrong if it's for a purpose, if it's to keep your nation free or protect your buddy. One of the most noble things you can do is kill the enemy.

Remembrances

From Marines At War, Stories from Afghanistan and Iraq:

CHAPTER ONE: CAPTAIN DOUG ZEMBIEC

BY SERGEANT MAJOR WILLIAM S. SKILES (RET)

Sergeant Major William S. Skiles served in the U.S. Marine Corps for 32 years. During his career, Skiles held a variety of positions including sniper instructor, reconnaissance platoon sergeant, Royal Marine exchange instructor, drill instructor, and Marine Corps rifle team shooter. He was decorated three times for his heroic combat actions during his deployment to Fallujah, Iraq, in 2004. The following story is focused on that deployment when he served as a first sergeant with Echo Company, 2d Battalion, 1st Marines. Skiles reflects on his relationship with company commander, Captain Douglas A. Zembiec, and on how Zembiec’s leadership, character, and humility influenced Skiles’s life, as well as the lives of all the Marines in Echo Company who saw combat together. Skiles received the Colonel Francis F. “Fox” Parry Writing Award for initiative in combat for his January 2008 Marine Corps Gazette article, "Urban Combat Casualty Evacuation,"" which covered the same time period depicted in this essay.

When the ramp drops tomorrow, who will come out? What type of human beings will come out? Will those humans honor their country, their corps, and more important, the Marines to their left and right? When the ramps dropped from the boats on the beaches of Iwo Jima, who came out? When the ramps dropped from the helicopters in Vietnam, who came out? Honorable warriors came out to uphold the virtues and values by their actions on the battlefield. This is our time and our legacy. This is our Vietnam. This is our Okinawa. Carry the honor and traditions that formed our great nation into battle. Climb aboard, Marines!

These were the words spoken by Captain Douglas A. Zembiec as he addressed his company of Marines before they entered the city of Fallujah, Iraq, in 2004. I was one of those Marines. Why were these words so important? Were these words a way to stop the hatred we felt against the individuals that killed four Americans the day prior? Was it because we had weapons in our hands and could take lives with one pull? Was it a reminder that regardless of what we all felt inside, our ethical and moral obligations to each other and this great country of ours should be paramount in our minds? By the captain’s words and, more important, his actions, we entered and left a battle with a clear conscience and a feeling that we did good in the face of extreme adversity. Whenever he spoke to us, we listened. From my first encounter with him, he had a certain way to make me believe in his actions and words.

I arrived to 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, on 12 October 2003, as a senior first sergeant. The sergeant major assigned me to Echo Company and paired me with Captain Douglas Zembiec. As I left the sergeant major’s office, he said, “good luck with that warrior of officers!” I did not know how to take the comment, but soon found out what he meant.

Though I did not know it at the time, meeting Captain Zembiec would change my life. As I walked into his office, he dutifully got up and offered the type of firm handshake I would expect of a Marine. He said, “First Sergeant Skiles, Bill, I’ve been waiting for your arrival, and we are going to do good things together.” I reviewed his vision for the 139-man infantry company he commanded, and we discussed how I could assist him to prepare the company for battle. He knew at that point that we were headed to a place in Iraq known as Fallujah. It seems funny today to think that, at the time, we had no idea where Fallujah was; it was just a mysterious place on a map. Our unit was to depart in late February 2004 and arrive in Kuwait. We would then head north to relieve the U.S. Army unit that was currently stationed there. This was going to be the first time the Marines traveled back to Iraq since President George W. Bush declared the end of combat operations in May 2003. Captain Zembiec also briefed me on the training that he would like our men to do, which was not necessarily the type of training the higher-ups wanted us to provide. Somehow, he knew we were not heading into a mop-up situation and that we needed to be prepared for combat.

As I left his office, the captain gave me a reassuring handshake and invited me to the evening’s social event at his house. He then asked me to bring my wife, Tanis, to this event so he could meet her. At that moment, I realized he had taken the time to find out my wife’s name before meeting me; this is something that not all leaders in the Marine Corps do.

Tanis and I arrived at the captain’s apartment in Mission Viejo, California. What was inside taught me the true meaning of strength through humility. After Tanis and I were introduced to others in the room, I wandered through the apartment, taking note of all the awards that were hanging on the walls. What Doug had accomplished was amazing. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1995 and was a two-time NCAA all-American wrestler. He also had experience with force reconnaissance, serving as a platoon commander in Bosnia, where he saw combat face to face. Prior to coming to 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, he had graduated from resident Expeditionary Warfare School (EWS) at Marine Corps Base (MCB) Quantico, Virginia, a school very few captains are selected to attend.

Why was I so surprised to learn of all Doug’s accomplishments? Mostly, I was impressed by his humility and the fact that he was never arrogant, despite his personal successes. If I had not visited his apartment that day, I may never have found out that he attended the Naval Academy or that he was a competitive athlete. It was as though he wanted to be just a Marine sharing an experience with other Marines without calling attention to his accomplishments. Humility was Doug Zembiec’s greatest strength, and in the next few months of training for Fallujah, he demonstrated this attribute in every way possible.

From October 2003 to February 2004, our battalion was in predeployment status, and we trained. For the most part, the training we received was typical; we attended hundreds of briefs about what to do and what not to do during deployment, and we participated in various work-up exercises. However, it was Captain Zembiec’s company training that made us lethal. Each morning, Doug would lead us through our physical fitness training regimen. Here are a few examples of Doug’s humility in action during this training. Because of his physical prowess, one might think Doug would always strive to be the first to finish the company runs and that he would mock the Marines who were not able to keep up with him. This is the typical “lead from the front” mentality that our young leaders are encouraged to employ. I learned from Doug, however, that true leaders finish in the middle. “How can a leader see what’s behind him if he finishes first?” he asked.

Unaware that Doug was an all-American wrestler in college, one of our bigger lance corporals challenged him to a grapple. Confident that Doug would win the match, I stood by to watch the spectacle. In a matter of three minutes, I learned again the lessons of humility from a captain of Marines, a true leader. He actually pretended to struggle and allowed the young Marine to pin him. As they both got to their feet, Doug embraced the Marine and said, “Great job, warrior. The enemy is in for it with strength like that.” The young Marine smiled and walked away proud. Doug knew something the rest of us did not. He understood the importance of being comfortable in his own skin. He always told me there is no need for showboating when you are comfortable with your strengths and flaws.

Doug only lost his temper with me once, but even then, he acted as a professional. It was a typical early morning workday, and we all came together for a company formation. The platoon sergeants and company gunny gave me the thumbs-up to let me know that everyone was in formation, and I took their word for it instead of double-checking to make sure all of the Marines were present. I walked down to the captain’s office to let him know that the company was standing by in formation. Yet my accounting of the Marines present was incorrect. Doug said a few words to the Marines of Echo Company and then met with the company officers, while I met with the enlisted. After the meetings, Doug called me into his office and asked me to close the door. When I turned around to talk to him, he was inches away from my face. He looked me straight in the eye and said, “Don’t you ever lie to me again!” All I could reply was, “Yes, sir.” He then turned and calmly asked, “What else do we have on the training schedule today?” Like a true professional, he did not allow his emotions to distract him from the mission. That day I learned two other attributes of leadership: accountability and passion.

One last highlight of our time together in predeployment training was during the regimental field mess night, at which all the Marines from 1st Marine Regiment broke bread, shared embarrassing stories from training, and drank alcohol until we all passed out in the brush. Over a few beers, Doug’s compassion and concern for the lives of our Marines was obvious. He shed a tear here and there, talking about what we would face and of his hope of bringing everyone home alive. Waking up after this event is something I will never forget because the scene was similar to events we would witness as we battled in Fallujah later that year. There were bodies everywhere! The smell of alcohol was apparent, and trying to find my Marines was difficult. In fact, we just let them sleep until they got up on their own.

Before we left Camp Pendleton for Kuwait, Doug got the unit together and had a contest. He said that whoever came up with the best company call sign would get time off. In response, a young lance corporal came up with the call sign, “War Hammer.” From then on, when we talked to one another on our radios, we would refer to each other as members of the War Hammer company. For instance, Doug answered to War Hammer 6 while I was referred to as War Hammer 8. On 29 February 2004, the Marines of War Hammer went to war.

Our flight to Kuwait was typically long with various stops and customarily poor service. We could not wait to hit the ground. We transferred all of our gear from the plane to buses and drove hours to our holding base to acclimatize. During the next couple weeks as we waited to make the long drive to Fallujah, Doug was the only company commander who had his Marines participate in daily physical training exercises. We also did company runs just to reinforce the idea that we were a tight-knit, well-oiled machine. I think other companies were jealous of the cohesion that existed between the Marines in our group. Doug and I always ate chow together, and we discussed, from time to time, our mission in this mystery city called Fallujah. Like all good Marines, we wanted a mission statement and commander’s intent that would outline the purpose of our mission, but we were not receiving that type of direction. During this time, we attended meetings about unit discipline around the camp. We were provided with long lists of regulations regarding the type of behavior that was appropriate at the joint military camp. However, there was very little planning taking place. It was as though going to Iraq was not the priority despite the inevitability of deploying to that place.

As we prepared to leave the camp and head north into Iraq, Doug and I agreed that what would take place next was the hardest thing we had to do in our entire time serving together. Our company was instructed to drive 36 vehicles across hundreds of miles of unsecured territory in Iraq. We were expected to have numerous attachments, and all of the Marines and vehicles were to arrive intact within three days.

First of all, most government vehicles were not well maintained. We had 7-ton trucks, jalopy-looking humvees, dump trucks that looked like they were from World War II, and fuel trucks that were already riding on spare tires. Doug and I did our best to organize this disaster and to develop security plans, breakdown plans, and troop issue plans. It was Doug’s passion and courage that ensured the success of this convoy from hell.

As we were driving to Fallujah, a U.S. Army unit with five vehicles decided to integrate into our convoy. Doug told the driver of our vehicle to speed up close to the Army unit and find the leader of this intrusive force. Our driver did exactly that. He cut off the Army vehicle, running into its side. A soldier got out of the Army vehicle and approached Doug, and immediately, a heated argument ensued. After a lot of shouting, the soldiers got back in their vehicles and stated they would continue to follow us, regardless of the concerns Doug had expressed. I could not believe what I saw next. As the soldiers attempted to drive away, Doug stood in front of their vehicle. The soldier then began to drive over Doug, so he leaped on the hood of the hummer and held on to the windshield wipers. The hummer took off, and we followed it for about a quarter mile before the soldiers pulled over. To my amazement, Doug was still attached to the hood! Even before the valor of combat, Doug showed his men that he was willing to stand his ground, no matter what the personal consequences.

Camp Baharia, located three miles from downtown Fallujah, was to be our home for the next seven months. When we arrived, the Army unit we were replacing taught us about the local populace, the terrain, improvised explosive device (IED) lanes, and areas to avoid. Doug and I both thanked the leaders of the unit for a great turnover and their professionalism, a welcomed contrast to the treatment we had received from the soldier who had attempted to run Doug over with the hummer.

It was not long before we had our first hostile encounter. On one of the last days of turnover from the Army, we were in downtown Fallujah conducting some grip and grins with the local town leaders. I was on top of a tall building, along with about 100 other soldiers and Marines. We were keeping watch and providing security in case there was an incident during the meetings. Doug was situated near the vehicles and was chatting with another member of our company. Without warning, a mortar round hit dead center in the middle of the company’s compound. Then, two more mortars hit around the compound, and one exploded where 10 Marines and soldiers were gathered. As chaos ensued, I had the chance to witness Doug Zembiec in action when lives were on the line.

Through my binoculars, I watched him leap over a high wall and run out to where 10 troops lay on the ground. All of them were crawling and were clearly injured by the mortar explosion. Without hesitation, Doug climbed up the stairs and carried the more severely wounded over the wall to safety. He made numerous trips, and only one other Marine helped get all 10 servicemembers back over the wall. Once the wounded were all together, some of our vehicles left to find medical help. By now, all of us on the rooftops were being shot at by small-arms fire, so we hunkered down and slowly made our way to the vehicles. Once all were accounted for, we drove out as well. I assisted at a point outside the city to render medical assistance as best I could. By the end of the day, 10 men were hit. There were no deaths, but the Marines accounted for 5 out of the 10 casualties, and it was only our tenth day in the country. As things calmed down, I remember Doug and I walking to the chow hall with blood on our boots and trousers. All Doug could tell me was that “it’s going to be a long seven months, and we better get a plan for more of the same.” When I got back to the hooch that I shared with Doug, I started writing down the heroics of this captain of Marines, mostly to never forget but also to tell everyone about this man and to be an eyewitness to greatness in the face of adversity.

During the next seven months, Doug’s words proved to be true. We saw too many skirmishes and heated exchanges of battle with the enemy to recall all of them, but I will try to capture the character and heroics of Doug Zembiec that stood out to me and all the Marines of Echo Company.

On 26 March 2004, the warriors of War Hammer headed into the city of Fallujah on foot. This would be the unit’s first true test of discipline in battle that Doug had prepared us for. The day before, a lone Marine was killed in the city, and our battalion’s response to this aggression was to send in a couple Marine companies to go fishing for insurgents. That day, alongside Doug, we battled insurgents street by street, block by block, and we controlled about one-third of the city—sharing this moment with Doug was an experience beyond description. His demeanor and patience under fire made the rest of us more confident. He never fired a shot but made his way down the streets, coolly and calmly using his radio to keep control of the three platoons. He was moving so quickly that the lance corporal radio operator was having difficulty keeping up with the good captain. It was only when we got word that one of our own had been wounded that a look of panic hit his face. I told him, “I’ve got this,” and “You keep the others in the fight.” He just gave me a thumbs-up, and I ran toward the area where the injured Marine was.

This Marine was shot in the hip and needed to be taken to Bravo Surgical Unit aboard Camp Fallujah, our main headquarters. I flagged down one of the Weapons Company vehicles and asked if they could assist. I took a door off the hinges of a hut nearby and placed the injured Marine on it. We then stuck the door and Marine in the back of the vehicle and headed back to our camp. This was the first of the 78 casualty missions that I went on for Doug and our Marines. After dropping off the Marine at medical, I went back out to rejoin the fight. I found Doug and gave him the thumbs-up to let him know the Marine was taken care of.

After this daylong battle, Echo Company fell back. We dug in around an area known as the cloverleaf. The next day, we learned that we had killed more than 20 enemy combatants, yet we had one Marine wounded. We waited for a counterattack that never came. After two days, Doug was frustrated by the lack of information we had gained, but he still felt that it would be foolish to just give up the ground. On the third morning, we were ordered back to our home, Camp Baharia. This is when Doug and I had a serious talk about what each of us would be responsible for. “Having one of our Marines down with no real medivac plan was stupid and reckless on our part,” Doug insisted. Then and there, we decided who would take the fight to the enemy and who would be responsible for the fallen.

Doug made sure I knew his appreciation for my efforts, and I would like to share what Doug wrote on my going-away plaque that he gave me on 12 December 2004, when we came home to the states and I was promoted to sergeant major. It reads,

From the Marines of War Hammer, you slayed the enemy when needed, and took care of our wounded, and for that we are brothers forever. May the memories of this company stay with you forever and ever and it’s been an honor to share the experience of valor and sacrifice with you. War Hammer 8, I salute you.

Things that Doug gave me and wrote for me, and items that we shared, are still in my heart and soul today.

As the month of April 2004 came, so did the sacrifice. After the American contractors were slain in the streets and hung on the bridge, we went back to this city of hell to stay for the entire month. What occurred during this month affected us, but most of all, it reinforced what Doug Zembiec instilled in us and how we knew things would work out so long as he was in the fight.

Echo Company fought the insurgents daily, and thank the Lord, they were lousy shots. We occupied houses on the edge of the city in an area known as Jolan Heights. We built up our positions, ready for a counterattack at every waking moment. The beautiful thing about having Doug as my company commander was that he always had time for me. Between firefights, we both agreed to sit down and document the heroics of our Marines that day. We focused on recording eyewitness statements that would hopefully reward these young Marines for their fearlessness in the face of the enemy and give credit where credit was due. By the end of our seven months in Iraq, our company had written more valor awards than all other companies combined. It was not because we saw more combat; it was because our company commander had the humility to remember daily the Marines in front of him and to make sure their stories were told. Doug got upset if a platoon commander put off writing about a Marine due to the commander’s fatigue, because he truly enjoyed writing about the heroics of his men and wished to write a book about them someday. In the same light of valor, we also had those who made the ultimate sacrifice. Doug confided in me a lot about his experience writing condolence letters to the families of our dead Marines. Knowing a grieving mother and father would receive these letters, he wanted to make sure they were the best he ever wrote. All in all, Echo Company had more than 78 dead and wounded Marines out of a company of 139. Some of these warriors were hit by enemy fire twice and still continued to fight. This is a true testament to how Doug Zembiec inspired his Marines through his leadership and humility. In honor of his heroics in battle, I wrote-up seven separate, heroicaction awards for Captain Doug Zembiec. I had hoped one of these writeups would make a difference. After all, if I did not record the heroics of my captain, who would? In fact, one event I described in one of these write-ups is portrayed on a statue that Marine Corps Special Operations Command (MARSOC) gives annually to its team leader of the year. Named after the brave captain who taught me so much during our deployment, this annual award became known as the Zembiec Award. Below is the citation I wrote to recognize Doug for his heroic actions:

April 6, 2004, Captain Doug Zembiec went above and beyond the call of duty. While in a static, defensive position, Echo Company came under a mortar and small-arms attack by a platoon sized insurgent element. Two U.S. M-1A [Abrams] Tanks were in support and as Echo received the fire, the two tanks went forward into the outskirts of the city laying supporting fires. The two tanks were using their main gun and machine gun to repel hostiles. Doug Zembiec noticed that the two buttoned up talks were firing at the wrong building, so he leaped forward, ran over two walls, and exposed himself to enemy fire as he approached the rear of one of the tanks. The tank phone was not quite working, so Doug had no other choice but to get on top of this moving and firing tank to try to get the commander’s attention and redirect their fire to where the insurgents really were. As enemy bullets ripped all around him, Doug banged on the hatch of the tank and the commander opened the hatch as to communicate with Doug. Doug used his knife hand to show the commander which building the enemy was in. Doug then took a magazine of tracers and fired these visible bullets into the building where the tank should be firing. As I looked on, the tank slowly rotated its main gun, and with Doug still on the back, the tank fired its main gun into the correct house. The intense blast and shock knocked Doug off his feet. Doug gave the thumbs-up to the commander and ran back to our lines. Due to his heroics, the bad guys quit firing and retreated as the tank finished off a couple more. The witnessing Marines all gave our Captain a high-five and there were smiles all around.

In October 2004, the warriors of Echo Company returned home. One of the proudest moments that Doug and I shared was when we got off the buses, formed the men up, and marched toward our waiting families. I remember seeing Pam, Doug’s fiancée, jumping into his arms and almost taking him down. We looked at each other, and I said, “See you tomorrow.” Then, in December, Doug and I parted ways. I was promoted and reassigned, and Doug had orders as well. We stayed in contact throughout the following months, and in mid-2005, I was honored to attend Doug and Pam’s wedding on the U.S. Naval Academy grounds. I toasted them and told some of the stories that Doug and I shared in our hooch in 2004. I spoke of how hairy this man was from the eyebrows down and of his obsessive need to keep his toenails clipped. I had a great time remembering the fun we had during the most difficult, but most rewarding, time in our lives. After the wedding, we lost touch for a bit. I learned that Doug volunteered for duty with special operations for the Marine Corps. The missions he was selected for are still unknown; what little I do know about what Doug was doing in Iraq I learned from Pam. The twelfth of May 2007 is the day I wept.

I was a sergeant major of a squadron of Marines, and I was doing my daily routine when I received a phone call. One of my former Marines from Echo Company asked if I had heard the news. I asked, “What news?” He replied, “Doug’s dead.” I wanted what I had just heard to be a bad joke. I sat down and asked, “How did he die? How do you know?” He said Doug had died the day before, but the Marine Corps had just received the news. All I could do was try to breathe. There was no way a goliath of a man like Doug could be dead. I said my thanks, hung up the phone, and sat silently for a few minutes. And then it came. I have never in my life experienced what I went through that day in my office. Rage and tears flowed to the point that I could hardly catch my breath. I wept for at least an hour before I composed myself enough to call my wife. I went home early that day and stared at nothing. Then, I received a call asking if I could fly to the Naval Academy to assist with Doug’s funeral.

I left that night for Annapolis, where I met up with others who were also shocked to hear the news of Doug’s death. Despite our grief, we knew we had to regroup to do this deed together. I shared the news of Doug’s death with the folks I met that day, and I think we all felt sorry for those who were not fortunate enough to have met Doug. We considered ourselves better for having been in his presence at one time or another. The things Doug’s friends and family said about him during his funeral will always stick with me. In a story recounted at Zembiec’s funeral and reported in coverage by the Washington Post, Zembiec and his father, Don, were driving on to Camp Pendleton and were stopped at the gate by a young Marine. “Are you Captain Zembiec’s father?” the Marine had asked. “Yes,” his father said. “I was with your son in Fallujah,” the Marine said. “He was my company commander. If we had to go back in there, I would follow him with a spoon.” Almost the entire Echo Company gathered at the Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, that day to say goodbye to the “Lion of Fallujah,” as we called him.

Doug told me one time that he really looked up to me and appreciated how I handled the Marines and their personal problems. It is funny to reflect on this conversation that I had with Doug, because for the rest of my life, I will look up to him. The following is what I wrote the night I heard about Doug’s death. It was originally sent as an e-mail, but it went viral to blog sites. It is the best way to conclude this essay about the life and work of Doug Zembiec:

I’m SgtMaj Bill Skiles, and I was Doug’s 1stSgt in Echo Co. in 2004 in Fallujah. I would like to tell you about the Doug Zembiec that you won’t read about in papers. I shared a hooch with this man for seven months and we would talk about everything from his Marines to what it will be like to be married. Doug was known for his tremendous warrior spirit and his physical strength. He was a physical specimen, but he had a heart of gold. The qualities that I still live with thanks to him are humility and sincerity, Doug would be the first to hug a PFC and tell him it’s OK, instead of putting him down for being weak. He would be the first person to stand up for you if he felt you were being treated unfairly. When he told someone he would do something, he did it and made sure you knew the results. He wouldn’t sleep until he knew you understood what was happening. Doug was confident is [in] his own abilities, and he had every right to be the most arrogant man alive. But he knew who he was and would always tell me that any leader who had to be arrogant towards his own Marines was probably thin skinned and insecure. He would call some of these Marines “junior varsity.”

Doug and I made a deal on the day our first wounded went down in late March ’04. The deal was that I would take care of and account for all wounded and he would keep the rest of the Marines focused on the fight. This agreement was made because he could not handle seeing his Marines bleeding and hurting. . . . He and I would weep behind closed doors during some of the trying times with mass casualties. Doug’s emotions were always worn on his sleeve, and I really admired that. His troops admired that. . . . He showed us all that he was human; he cared deeply about us and felt what we felt. ALL of his troops would have given their lives for Doug if needed; I cannot name another commander who could say that. He wasn’t fake; he wasn’t the most politically correct officer, but the troops that walked the streets with him and fought and sacrificed with him understood. That bond is hard to teach any ego. . . . I wish all commanders could learn just a little of the humility and sincerity this warrior displayed daily to every Marine, regardless of rank. Doug’s Marines loved to laugh with him, cry with him, and mostly, to fight and kill the enemy with him. Every Marine knew that when Doug showed up to a fight, things were going to be ok.

Doug allowed the chaplain to perform services during firefights, comforting our grieving warriors after loss. He listened to our corpsman about how to take better care of the fallen. From his firm handshake to a grieving hug, I will miss him until I join him. I will miss this man, the hairiest man on earth from the eyebrows on down. The poor guy had no hair above his eyebrows, but he was a human woolly pulley every where [sic] else. He would try to shave his back before patrols and always missed various spots. And yes, I would help finish the job. What are buddies for? Doug Zembiec would never talk about himself, about what’s he done, about any of his accomplishments, because he told me that no one really cares about what you have done. As you command, the Marines want to know what you can do now and [in] the future. Well said! The day Doug received his Bronze Star with “V”, he wept. I wept and I hugged this warrior and no words were spoken . . . I know why we wept. We would talk over and over again about how with valor comes sacrifice, but he thought this valor medal would never match the sacrifice that his Marines went though [sic]. Humility again shows itself.

About his new family: Doug LOVED Pam and being a dad made him even more humble. His daughter’s birth was the proudest day ever for him. Until that day, he told me the proudest moment in his life was leading the Marines of Echo Co in battle. I could talk for days about how much this man meant to me and to his Marines, but I know this man was the definition of what a Marine should be, what a committed husband and father should be, and what this country looks for in a true hero in every sense of the word. I will spend a couple hours with him tomorrow night when it’s my turn to watch over his body, and we will finish what we talked about for those seven months. I love you, Doug Sgt Maj Bill Skiles

In Chapter Eleven, "A PERSPECTIVE ON LEADERSHIP ATTRIBUTES IN COMBAT," author Major Benjamin P. Wagner (USNA 2002) mentions Doug repeatedly:

As a second lieutenant, I learned much about grace and leadership while serving under then-Captain Douglas Zembiec in Echo Company, 2d Battalion, 1st Marines.6 We deployed to Fallujah, Iraq, and fought and served there from March through October 2004. We were taking part in Operation Vigilant Resolve in response to, among other things, the murder and mutilation of four Blackwater security contractors on 31 March. Our battalion, along with three others, pushed into the city to regain control and solidify the hold by the legitimate government of Iraq. Despite the political unrest and back and forth at the highest levels, we were in a fight and no cease-fire was honored by the insurgents in the city. During these formidable seven months, I learned some of the most heart-wrenching lessons through personal experience.

On 26 April 2004, following a firefight during which a Marine in my platoon was killed, my company commander sought me out because he knew I was in need of some focused leadership. He knew that my virtual tank was running low and that I was frustrated with the continued losses in my platoon. It seemed as though my platoon in particular was continually getting into firefights that resulted in the wounding or death of wonderful, strong, young warriors. Due to the nature of urban fighting, the combat was close and personal; we could hear and see our enemies just feet away, at times, as they sought vantage points from which to fire on us.

On this particular day, the fighting had been very heavy. The regimental operations officer told me, some time later, that he had seen more than 100 insurgents move toward our platoon’s position while watching the fight on a live feed from an unmanned aerial vehicle. Two Marines held the enemy from breaching into our strongpoint by dropping hand grenades over the side of the roof. Another Marine used his M249 squad automatic weapon from an exposed position in the street to cut down insurgents moving in the open. While evacuating several of our wounded comrades, two Marines used their automatic weapons and an M203 grenade launcher to devastate insurgents firing on us from an adjacent building. Personal heroic action in this firefight resulted in my Marines receiving three Silver Stars, four Bronze Stars, and numerous other valor awards. Of the 24 Marines and corpsmen in my platoon, 11 were wounded on that day. It was a tough fight, and my brain and body were drained and tired.

Several years later, when I was a staff platoon commander at TBS, I began to fully understand what my company commander did for me following that fight. At that time, one of the required readings for the lieutenants was Passion of Command by Colonel Bryan P. McCoy. A short book with many valuable leadership and training lessons, there was one particular passage that speaks directly to what Doug Zembiec did for me on 26 April 2004. In the book, Colonel McCoy discusses the “well of fortitude.”7 Though he borrowed the idea, he did a very good job of explaining the role of a tactical leader to manage the well for his or her subordinates. My well was running dry, and I needed a more experienced leader to help me find a source of strength to overcome the challenges I was facing on a daily basis.

Doug told me that aggressive first and second lieutenants needed to be tempered by experienced captains and that experienced captains needed to be tempered by judicious lieutenant colonels. He let me know that I was making the right decisions and that my Marines were doing exactly what they were supposed to be doing. Moreover, we had trained the men well, and they were taking the fight to the enemy and effectively killing them in every engagement. He told me that casualties happen, and as long as I was employing my Marines and their weapons appropriately, I must be proud of their sacrifices and rejoice in the efforts they put forth to fight and win with dignity and honor. I would not fully understand the lesson he taught me that day until it was my place to fortify junior Marines and sailors in future combat deployments.

Captain Zembiec demonstrated grace toward me in the attitude he took to understand the pressures I was facing and to reach out to me in a way that showed he could accurately grasp the complex challenges of being a young platoon commander. He did not tell me to suck it up or to be harder or that I was weak for worrying about casualties. He let me talk and he reinvigorated my soul, thereby making me a more effective combat leader. His example of grace instilled in me a greater confidence in his leadership and a better understanding of what he wanted from me. It made clear to me that his expectation was that I continue challenging the enemy, while pressuring the insurgents at each and every opportunity. He inspired me to continue pushing my Marines, but he did so with compassion and an understanding that communicated to me that he was fully aware of what we were doing and how that taxed our well of fortitude. Through his personal example, he inspired me to continue striving for greater levels of effectiveness and success in combat.

From the Naval Academy Alumni Association's updated "In Memoriam" page:

He was the consummate warrior… absolutely magnetic. He was a great inspiration, an absolute role model for every one of the Marines he served with. He would walk into a unit and literally stun every Marine. They would look at him and say, “My goodness, we got this guy?” Colonel John Ripley '62, USMC (Ret.)

From an article commemorating the 15th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks authored by Captain David Poyer '71, USNR (Ret.) in the September-October 2016 of Shipmate:

Born in Kealakekua, HI, the son of an FBI special agent and a grade school teacher, Douglas Alexander Zembiec attended La Cueva High School in Albuquerque, NM. There, he was a state wrestling champion, undefeated in his senior year.

At the Naval Academy, Zembiec majored in political science and continued to wrestle. He was a two-time NCAA All-American wrestler, a Naval Academy Athletic Association Senior Award Winner at graduation (winning three varsity letters in one sport and participating in that sport for four years) and won the Ed Peery Wrestling Award in 1995 for demonstrating outstanding leadership, dedication and competitive spirit in the wrestling team.

Zembiec always pushed himself and his friends, challenging them to do more than they thought possible. His classmate and fellow wrestler Andre Coleman ’95 recalled: “ … during one of our pre-practice runs we were running from Lejeune to the blinking light up 450 near the intersection of 301/50. Being one of the bigger guys I was lagging towards the back of the group, but Doug stayed back to push me on. On the way back we were making great pace, as we crossed the old Severn River Bridge, Doug looked at me and said we can beat everyone back if we swim to the Yard from here. Before I could even contemplate the implications he was over the rail and in the water, realizing that I would much rather swim than run another mile I was in the water right behind him. Needless to say it took us much longer to swim to the Yard than we planned and we therefore were back in the wrestling room only minutes before we had to strap on wrestling shoes and hit the mat.”

Zembiec service-selected for the Marine Corps. He served as a Force Reconnaissance platoon commander, being one of the first to enter Kosovo in 1999 as part of Operation Joint Guardian. He deployed to Iraq in Operation Enduring Freedom before taking command of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division in July 2003. He returned to the special operations community in 2004.

The city of Fallujah had been a thorn in the side of the Coalition for years. The mainly Sunni population had not taken well to the democratic handover of the country to the Shia-majority interim government. The first Battle of Fallujah (spring 2004), also known as Operation Vigilant Resolve, began with the killing of four U.S. security contractors, mutilated and hung on the Highway 10 bridge in west-central Fallujah. Beginning 6 April, Echo Company was among those sent in to root out insurgents, launching a month of intense street fighting.

Bing West, a reporter embedded with Zembiec’s unit, called him “ … a wild man, terrific in a firefight and brimming with enthusiasm.” “ … Doug Zembiec had a manic grin, as if he wanted to spring up and grab you in a bear hug, maybe breaking a rib by accident, just for the hell of it. ‘I’m never so alive,’ he told me, ‘as in a firefight. Time slows down for me. I can see it all, sense what they’re going to do next.’”

He and his Marines fought hard, taking heavy casualties and inflicting many more. Zembiec “led from the front, rallying his men and directing fire even after being wounded.” Captain Ben Wagner ’02, USMC, described how in his first firefight, he “looked across the line of fire, and Captain Zembiec stared back at me and smiled—a reminder that everything was going to be okay.”

Along with the Purple Heart, “Zembiec was also awarded the Bronze Star for valor for rushing into the middle of a machine-gun-raked street to get the attention of an Abrams tank supporting Echo Company … for whatever reason the radio, or ‘grunt phone,’ wasn’t working, so Zembiec scaled the tank while bullets ricocheted off its hull. After he knocked on one of the hatches repeatedly, the crew of the tank finally opened up. Zembiec then loaded a magazine of illuminated tracer rounds and began shooting from the top of the tank to mark the building from which his Marines were being shot. The tank swung its turret and without warning fired its massive 120mm gun. The blast threw Zembiec into the air and onto the street below.”

For his actions in Fallujah, Zembiec was awarded the Bronze Star with valor device and his first Purple Heart.

In interviews, he often said his men had “fought like lions.” The title became his: “The Lion of Fallujah.”

This first battle ended with a coalition withdrawal in favor of an Iraqi-run security force. But that soon crumbled, leaving the city at the mercy of criminals, warlords and ‘Takfiris’—foreign, largely Al-Qaeda-linked radical Islamists—who earned Fallujah the title “the bomb factory.” It became “a safe haven for foreign fighters, terrorists and insurgents, “a ‘cancer’ on the rest of al-Anbar Province.”

The Second Battle (Operation Phantom Fury) took place in November and December, when the U.S. Army, Marines, Iraqis and British were ordered in. Their opponents were two to three thousand local insurgents and foreign fighters, stiffened by Chechens who had fought the Russians in Grozny. Many were foreign extremists who were more than willing to be martyred. The six-month withdrawal had permitted them to train, recruit, dig trenches, build defensive berms and roadblocks, prepare VBIEDs [vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices, or car bombs], and emplace mines and daisy chains of IEDs. On 8 November, the attack began. Marines cleared buildings room by room behind heavy Army armor. It was called “some of the heaviest urban combat U.S. Marines have been involved in since the Battle of Hue City in Vietnam in 1968.” Over the entire Fallujah campaign in 2004, 151 Americans died.

After turning over command, Zembiec was assigned as assistant operations officer at the First Special Operations Training Group, ostensibly conducting pre-deployment training for deploying Marines. He left there for duty at Headquarters, Marine Corps (HQMC) in mid-2005 and was promoted to major that July. That same year, he married and started a family, wife Pamela and daughter Fallyn.

But the official records don’t tell the whole story. Actually, Zembiec never did any staff work at HQMC, nor did he hold a staff position there. That was a cover for his real assignment, to a highly competitive position in the Ground Branch of the CIA’s Special Activities Division. “He went for this with all of his guts and glory,” Pamela Zembiec said. “I’ve never seen this man stressed in my life until he started interviewing for this. He was pacing, and he couldn’t sleep.” Accepted, he deployed to Afghanistan, then volunteered again to return to Iraq, his fourth deployment to that country, this time to fight not beside Marines, but with Iraqi forces.

On 11 May 2007, Zembiec was leading his unit on a raid in Baghdad. “Family members and former intelligence officials say Zembiec was working with a small team of Iraqis on a ‘snatch and grab’ operation targeting insurgents for capture. Just moments after warning his men that an ambush was imminent, he was shot in the head by an enemy insurgent; he died instantly … In the ensuing gun battle, the Iraqis serving beside Zembiec radioed back, ‘Five wounded, one martyred,’ according to battle reports.” His posthumous citation for the Silver Star read, “Attacking from concealed and fortified positions, an enemy force engaged Major Zembiec’s assault team, firing crew-served automatic weapons and various small arms. He boldly moved forward and immediately directed the bulk of his assault team to take cover. Under withering enemy fire, Major Zembiec remained in an exposed, but tactically critical, position in order to provide leadership and direct effective suppressive fire on the enemy combatant positions with his assault team’s machine gun. In doing so, he received the brunt of the enemy’s fire, was struck and succumbed to his wounds.”

Perhaps the hardest person for any officer to impress is his or her chief or sergeant. In Zembiec’s case, his company first sergeant in Fallujah, Bill Skiles, was won over. Skiles said, “He could not handle seeing his Marines bleeding and hurting … He and I would weep behind closed doors during some of the trying times with mass casualties. Doug’s emotions were always worn on his sleeve and I really admired that … I cannot name another commander that all of his troops would give their lives for if needed.”

“Doug’s Marines loved to laugh with him, cry with him and mostly fight and kill the enemy with him … and every Marine knew that when Doug shows up to a fight, it makes them feel a little better. Doug allowed the chaplain to perform services during firefights, comforting our grieving warriors after loss and listened to our corpsman on how to take better care of the fallen … From his firm handshake to a grieving hug together, I will miss him until I join him. I will even miss the hairiest man on earth, from the eyebrows on down … Poor guy had no hair above his eyebrows but he was a human woolly pulley everywhere else. He would try to shave his back before patrols and always miss various spots and yes, I would help finish the job … What are buddies for?”

Colonel John W. Ripley ’62, USMC (Ret.), one of those who called on Pamela Zembiec to tell her of her husband’s death, said Zembiec was “absolutely magnetic.” “He was a great inspiration, an absolute role model for every one of the Marines he served with,” said Ripley, a hero himself who blew up the bridge at Dong Ha in Vietnam. “He would walk into a unit and literally stun every Marine. They would look at him and say, ‘My goodness, we got this guy?’”

Zembiec is commemorated by a star chiseled into the Memorial Wall at the CIA headquarters in Langley, VA, and inscribed in the CIA’s Book of Honor. The NCAA awarded him the 2008 Award of Valor. The swimming pool located at the Marine Corps’ Henderson Hall is named in his honor, and the Commandant of the Corps annually presents the Douglas A. Zembiec Award for Outstanding Leadership in Marine Forces Special Operations Command.

Silver Star

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America takes pride in presenting the Silver Star (Posthumously) to Major Douglas Alexander Zembiec, United States Marine Corps, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy while serving as a Marine Advisor, Iraq Assistance Group, Multi-National Corps, Iraq, in support of Operation IRAQI FREEDOM on 11 May 2007. Attacking from concealed and fortified positions, an enemy force engaged Major Zembiec's assault team, firing crew-served automatic weapons and various small arms. He boldly moved forward and immediately directed the bulk of his assault team to take cover. Under withering enemy fire, Major Zembiec remained in an exposed, but tactically critical, position in order to provide leadership and direct effective suppressive fire on the enemy combatant positions with his assault team's machine gun. In doing so, he received the brunt of the enemy's fire, was struck and succumbed to his wounds. Emboldened by his actions his team and supporting assault force aggressively engaged the enemy combatants. Major Zembiec's quick thinking and timely action to re-orient his team's machine gun enabled the remaining members of his unit to rapidly and accurately engage the primary source of the enemy's fire saving the lives of his comrades. By his bold initiative, undaunted courage, and complete dedication to duty, Major Zembiec reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service.

Action Date: May 11, 2007

Service: Marine Corps

Rank: Major

Battalion: Headquarters Battalion

Division: Marine Corps National Capital Region

Douglas is one of 6 members of the Class of 1995 on Virtual Memorial Hall.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.