NORMAN SCOTT, RADM, USN

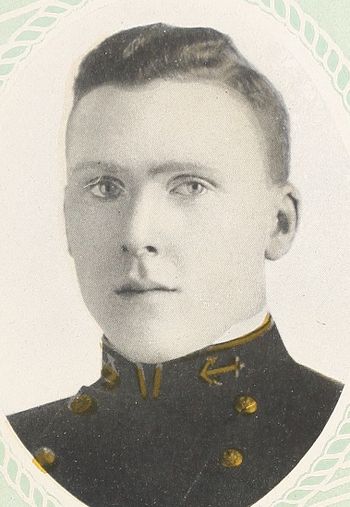

Norman Scott '11

Lucky Bag

From the 1911 Lucky Bag:

Norman Scott

Indianapolis, Indiana

"Norm" "Scotty"

A PERFECT non-greaser, a good fellow, and, therefore, one of the best liked men in the Class. Has friends of his own, and it's hard to get in, but once you do Scotty will treat you right. He has a brace like a camel, which helps to distinguish him from the ordinary run of midshipmen. On account of having been the wife of the Wop, he has always had to fight for a 2.5, but manages to keep his head just above water. Obtained immortal fame by helping to beat the Army in fencing in New York, when he became one of the three intercollegiate champions. He was second choice for individual champion. You never see Scotty without his sea-going pipe. Started at one time to fuss, but for reasons unknown, he cut it out. We wish Scotty only the best and when a showdown comes we know he will make good.

Gray N Star; Class Pipe Committee; White Numerals; Yellow Numerals.

Norman Scott was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, August 10, 1889. He was appointed by Senator Beveridge after completing three years in the Shortridge High School. His present home address is Indianapolis, Indiana.

Norman Scott

Indianapolis, Indiana

"Norm" "Scotty"

A PERFECT non-greaser, a good fellow, and, therefore, one of the best liked men in the Class. Has friends of his own, and it's hard to get in, but once you do Scotty will treat you right. He has a brace like a camel, which helps to distinguish him from the ordinary run of midshipmen. On account of having been the wife of the Wop, he has always had to fight for a 2.5, but manages to keep his head just above water. Obtained immortal fame by helping to beat the Army in fencing in New York, when he became one of the three intercollegiate champions. He was second choice for individual champion. You never see Scotty without his sea-going pipe. Started at one time to fuss, but for reasons unknown, he cut it out. We wish Scotty only the best and when a showdown comes we know he will make good.

Gray N Star; Class Pipe Committee; White Numerals; Yellow Numerals.

Norman Scott was born in Indianapolis, Indiana, August 10, 1889. He was appointed by Senator Beveridge after completing three years in the Shortridge High School. His present home address is Indianapolis, Indiana.

Loss

Norman was lost when USS Atlanta (CL 51) was destroyed on November 13, 1942 during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. The ship was scuttled following damage from Japanese torpedoes and gunfire from USS San Francisco (CA 38).

Other Information

From Wikipedia:

Scott was born August 10, 1889 in Indianapolis, Indiana. Appointed to the Naval Academy in 1907, he graduated four years later and received his commission as ensign in March 1912. During 1911–13, Ensign Scott served in the battleship USS Idaho (BB-24), then served in destroyers and related duty. In December 1917, he was executive officer of USS Jacob Jones (DD-61) when she was sunk by a German submarine and was commended for his performance at that time. During the rest of World War I, Lieutenant Scott had duty in the Navy Department and as Naval Aide to President Woodrow Wilson. In 1919, while holding the temporary rank of lieutenant commander, he was in charge of a division of Eagle Boats (PE) and commanded Eagle PE-2 and Eagle PE-3.

During the first years of the 1920s, Norman Scott served afloat in destroyers and in the battleship USS New York (BB-34) and ashore in Hawaii. From 1924 to 1930, he was assigned to the staff of Commander Battle Fleet and as an instructor at the Naval Academy. He commanded the destroyers USS MacLeish (DD-220) and USS Paul Jones (DD-230) in the early 1930s, then had further Navy Department duty and attended the Naval War College's Senior Course. After a tour as executive officer of the light cruiser USS Cincinnati (CL-6), Commander Scott was a member of the U.S. Naval Mission to Brazil in 1937–39. Following promotion to the rank of captain, he was commanding officer of the heavy cruiser USS Pensacola (CA-24) until shortly after the United States entered World War II in December 1941.

Captain Scott was assigned to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations during the first months of 1942. After becoming a rear admiral in May, he was sent to the south Pacific, where he commanded a fire support group during the invasion of Guadalcanal and Tulagi in early August. Rear Admiral Scott continued to lead surface task units for the next three months, as the campaign to hold Guadalcanal intensified. He was present during the Battle of Savo Island on the cruiser USS San Juan (CL-54), albeit miles from the action. In September 1942, he was named commander of Task Force 64, a mixed Cruiser-Destroyer surface warfare unit. The combat-minded, pugilistic Scott thoroughly trained and drilled his combat group in gunnery, maneuvers, and night fighting . This training paid off when, on 11-12 October 1942, he led his force to victory in the Battle of Cape Esperance, the U.S. Navy's first surface victory of the campaign. He maneuvered his ships so as to successfully perform the classically desired "Crossing the T" of the opposing Japanese force.

A month later, on November 13, he was second-in-command during the initial night action of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Many felt, at the time and with hindsight, that the fighting-minded and experienced Scott would have made a more effective overall commander of the US force than inexperienced first-in-command Daniel J. Callaghan did, and that Scott perhaps would not have made some of the mistakes that Callaghan did. Regardless, in that wild and brutal fight, Rear Admiral Norman Scott was killed in action when the bridge of his flagship, the light cruiser USS Atlanta (CL-51), was smashed by gunfire, possibly by "friendly fire" from Callaghan's flagship, the heavy cruiser USS San Francisco (CA-38), which joined with an enemy torpedo to fatally damage the Atlanta. For his "extraordinary heroism and conspicuous intrepidity" in the October and November battles, he posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

From researcher Kathy Franz:

When Norman was a pupil at School No. 32, he would learn healthful exercises at Captain Wallace Fosters’ home each afternoon after school. In a letter to the editor in December 1917, Foster reported that the group would drill in the maneuvers of the soldiers, and Norman was quick to learn.

In the spring of 1905, Norman played first base for the Shortridge baseball team. In football, he was the strongest lineman, and he was treasurer of the junior class. In April 1906, Norman was captain of the baseball team when he left for Annapolis.

At Annapolis, he pitched for the plebe baseball team in the summer of 1906 and won the game 1-0 with a home-run hit. He also played full-back on the varsity football squad in the fall.

In April 1910, Norman won the fencing bout for the navy in a contest in New York between the Navy, the Army, and the Pennsylvania and Cornell universities.

Norman was navigator and second in command of Jacob Jones which was sunk on December 6, 1917. In 1918, he was made the naval aide to President Wilson.

On October 27, 1921, Norman married Marjorie Guild in St. Andrew’s cathedral in Honolulu. Their son Norman Jr. (Class of 1944) became an aviator. Their son Michael was on Admiral Hewitt’s staff in 1946.

In December 1939, Norman sailed from Los Angeles to Honolulu. His name appeared on a ship’s list to leave Pearl Harbor on January 22, 1942, for San Diego.

Norman’s father Robert was in the grain business. His older brother William was a graduate of West Point.

From The Charlotte Observer, November 30, 1942, by Tom Yarbrough:

An Advance Base in the Solomon Islands Area, Nov. 17.

The death of Rear Admiral Norman Scott in battle off Guadalcanal in the early hours of last Friday, Nov. 13, deprived the United States navy of a fighting admiral whose ships had become known as “Scott’s Night Raiders.”

He was last seen standing on the bridge of a cruiser, binoculars to his eyes, watching the first phase of an uneven conflict with bigger Japanese guns.

A shell hit the bridge, killing nearly everybody on it. If I hadn’t run out of money a few days before and left the ship to cable for more, I would have been with him on the bridge.

On other missions with Admiral Scott, I had observed how keenly he was admired by the men of the fleet as a fighting admiral and as a friendly, plain-spoken and down-to-earth gentleman. He was the embodiment of the offensive spirit – a factor vital against an enemy as bold as the Japanese.

His force became known as Scott’s Night Raiders in a battle sector where the Japanese preferred to strike at night.

Scott left Washington only last June and achieved flag (rear admiral) rank shortly afterward. At the start of the war in the Pacific, he commanded a cruiser. Then he was called to Washington for a brief spell at a desk job.

Back on sea duty, he soon enhanced his reputation as a striking admiral. I first heard of him early in October when I happened to be on a cruiser that wasn’t having luck running into anything that would make newspaper copy. An officer said, “Why don’t you get with Admiral Scott?”

At the next port, I missed his force by one day – the time it seriously damaged a force of Japanese cruisers and destroyers by night in the second battle of Savo island.

I caught up with him a couple of weeks later and sure enough he was in pursuit of a sizable Japanese force, possibly one bigger than his own. He told me about the second battle on Savo island and blessed his luck. He caught the enemy completely by surprise. He insisted on giving the captains of all his ships major credit for the victory.

“All I did was lead them in,” he said.

Returning to the problem at hand, he said: “This is a tough one but we’ll see what we can do.”

His flag secretary confided: “History is going to be made tonight.”

A message from Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the United States Pacific fleet, was relayed to all hands. “Your comrades away from the battle scene are cheering for you. Good luck.” admiral’s message said.

For several hours it looked like yes or no for big stakes, but the opposing forces never made contact.

A few mornings later, we streamed along the north coast of Guadalcanal giving the Japanese land positions there the heaviest and longest bombardment of the war up to that time. It lasted two hours and 15 minutes. When it was over, Admiral Scott looked for another place to strike. He had no hesitancy about going in with inferior numbers and size.

He was a stickler for accuracy in reporting and believed in the strictest enforcement of regulations. One day I went into a certain part of the ship without knowing it was barred to correspondents. The admiral promptly gave me a dressing down. But we were still friends and, a little while later, he was speaking with warmth and brilliance about books and ships and other reporters he had known.

Unlike many senior naval officers, he spoke as plainly as the people you hear on street corners of small towns. Perhaps that was due to his Hoosier background. He came from Indianapolis but more recently called Washington, D. C., his home.

In the first World War, Admiral Scott, then a junior officer, commanded the destroyer Jacob Jones in patrol off southern Ireland, and he was on that ship when she was torpedoed.

He deeply respected his men and they followed him proudly. The feeling that existed throughout ships he commanded was well illustrated by the remarks of a young shell-handler who had exhausted himself while passing up ammunition to bombard the Japs on Guadalcanal.

“I’m so tired I can hardly move,” the youth said, “but we got a ‘well done’ from Admiral Scott and that’s good enough for me.”

From The Honolulu Advertiser, May 24, 1944, by Ray Coll, Jr.:

At A U. S. Naval Station in the Marshalls –

. . . I was catching a plane that morning and had to be over at the airport in an hour. “Come over to the signal tower when you’re dressed and I’ll have some hot coffee for you, “the voice said. . .

I dressed and went across the street. Signalman 2/c John E. Hamadock was waiting for me with hot coffee.

“I did a hitch in the Navy back in the early twenties,” he said, “and got out in 1923. I’m 43 now and have a wife and four children. My home’s in Elizabeth, Pa., just outside Pittsburgh.” He paused for a moment and then asked half shyly if I thought I could do him a favor. It was like this, he said. When he finished his last hitch back in ’23 his commanding officer was Lt. Comdr. Norman Scott of the old USS Burns. “He was the greatest guy I ever knew,” Hamadock continued, “and when I learned he had been killed down in the South Pacific I felt I’d like to enlist again and in some small way do my part in repaying the Japs for Admiral Scott’s death. I figured I owed him a debt for the many fine things he had done for me and other members of his crew. My wife didn’t want me to go . . .

“Well, I went out and enlisted and my wife got a job in a war plant . . . What I meant by a favor, well – when we took this place I recovered some papers which I figured had some valuable military information and turned them over to my officers. The other day I got a letter commending me and the letter indicated the papers were valuable, all right. What I mean is, if you could mention this in the paper someway and my wife would see it she’d know I’m really doing my bit and my enlistment wasn’t a foolish thing to do like she said. I feel like I’ve already paid back some of that debt to Admiral Scott.”

I said I’d see what I could do and told him I had known Norm Scott years ago and recalled him as a fine man.

And that is why I have written this little piece about an old Navy man who wanted to repay a debt. His sincerity was evident and I got kind of a lump in the throat as we stood there in the half light talking. He wasn’t a very big fellow, just average height and balding and his face was lined with the care of raising a family of four and it was tanned and leathery from the wind and sun. . .

He kept referring to the late Norman Scott and you could see he had been devoted to him. Said he used to get a letter from him once in a while. “He never forgot the men who had served under him,” he said simply. “That’s why I just couldn’t let him down and I hope wherever he is he knows I’m back doing my small part. . .”

His wife, Marjorie, was listed as next of kin; he was also survived by his son. Norman has a memory marker in Indiana.

Photographs

Medal of Honor

From Hall of Valor:

The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pride in presenting the Medal of Honor (Posthumously) to Rear Admiral Norman Scott (NSN: 0-7749), United States Navy, for extraordinary heroism and conspicuous intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty during action against enemy Japanese forces off Savo Island on the night of 11 - 12 October and again on the night of 12 - 13 November 1942. In the earlier action, intercepting a Japanese Task Force intent upon storming our island positions and landing reinforcements at Guadalcanal, Rear Admiral Scott, with courageous skill and superb coordination of the units under his command, destroyed eight hostile vessels and put the others to flight. Again challenged, a month later, by the return of a stubborn and persistent foe, he led his force into a desperate battle against tremendous odds, directing close-range operations against the invading enemy until he himself was killed in the furious bombardment by their superior firepower. On each of these occasions his dauntless initiative, inspiring leadership and judicious foresight in a crisis of grave responsibility contributed decisively to the rout of a powerful invasion fleet and to the consequent frustration of a formidable Japanese offensive. He gallantly gave his life in the service of his country.

Service: Navy

Division: U.S.S. Atlanta (CL-51)

The medal was presented by President Roosevelt to Norman's son, Norman Scott, Jr., then a Naval Academy midshipman, on December 9, 1942.

The "Register of Commissioned and Warrant Officers of the United States Navy and Marine Corps" was published annually from 1815 through at least the 1970s; it provided rank, command or station, and occasionally billet until the beginning of World War II when command/station was no longer included. Scanned copies were reviewed and data entered from the mid-1840s through 1922, when more-frequent Navy Directories were available.

The Navy Directory was a publication that provided information on the command, billet, and rank of every active and retired naval officer. Single editions have been found online from January 1915 and March 1918, and then from three to six editions per year from 1923 through 1940; the final edition is from April 1941.

The entries in both series of documents are sometimes cryptic and confusing. They are often inconsistent, even within an edition, with the name of commands; this is especially true for aviation squadrons in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Alumni listed at the same command may or may not have had significant interactions; they could have shared a stateroom or workspace, stood many hours of watch together, or, especially at the larger commands, they might not have known each other at all. The information provides the opportunity to draw connections that are otherwise invisible, though, and gives a fuller view of the professional experiences of these alumni in Memorial Hall.

January 1914

January 1915

January 1916

January 1917

March 1918

January 1919

January 1920

January 1921

January 1922

May 1923

July 1923

September 1923

November 1923

January 1924

March 1924

May 1924

July 1924

September 1924

November 1924

January 1925

March 1925

May 1925

July 1925

October 1925

January 1926

October 1926

January 1927

April 1927

October 1927

January 1928

April 1928

July 1928

LCDR Albert Rooks '14

LCDR Cassin Young '16

LT John Gillon '20

LT John Burrow '21

LT Joseph Hubbard '21

LT Edwin Crouch '21

LTjg Howard Healy '22

LTjg William Ault '22

October 1928

January 1929

April 1929

July 1929

October 1929

January 1930

April 1930

October 1930

January 1931

April 1931

July 1931

October 1931

January 1932

April 1932

October 1932

January 1933

April 1933

July 1933

October 1933

April 1934

July 1934

October 1934

January 1935

April 1935

October 1935

January 1936

April 1936

July 1936

January 1937

April 1937

September 1937

January 1938

July 1938

January 1939

October 1939

June 1940

November 1940

April 1941

Related Articles

Stanton Kalk '16 was also aboard Jacob Jones when she was torpedoed in 1917.

Namesakes

From Wikipedia:

The U.S. Navy ships USS Norman Scott (DD 690), 1943–1973, and USS Scott (DDG 995), 1981–1998, were named in honor of Rear Admiral Scott. The Scott Center Annex, adjacent to Norfolk Naval Shipyard in Portsmouth Virginia, is named for him. The Norman Scott Natatorium at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland is named for him for being instrumental in introducing intercollegiate swimming to the Naval Academy as a midshipmen. Norman Scott Road on Naval Base San Diego also honors his memory.

USS Norman Scott (DD 690) was sponsored by his widow.

The "category" links below lead to lists of related Honorees; use them to explore further the service and sacrifice of alumni in Memorial Hall.